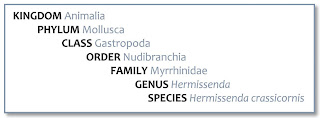

Eyes Under Puget Sound — Critter of the Month

This month’s aquatic critter looks like a luminous holiday spirit carrying dozens of flickering candles. Definitely don’t try this at home, no matter how festive the effect might be!Glow your own way

|

|

Hermissenda crassicornis from Hurst

Island,

British Columbia. Photo courtesy of Kevin Lee, diverkevin.com. |

The northern opalescent nudibranch has been called the most beautiful invertebrate in Puget Sound, and it’s easy to see why. Outshining its drab land slug cousins, this “sea slug” seems to radiate its own glowing light. With variable blue, orange, and snow-white markings, it’s ready for a holiday party! However, it’s more of a warm-weather fan, commonly found during spring and summer on intertidal and shallow subtidal habitats. These include mud flats, eelgrass, dock pilings, and rocky pools.

Mistaken identity

The northern opalescent nudibranch, or Hermissenda crassicornis, was once thought to occur all over the west coast. But in 2016, genetic analyses revealed that there were actually two west coast species: H. crassicornis, occurring from Alaska to northern California, and H. opalescens, occurring from northern California to Mexico. The southern species appears the same, but it doesn’t have white lines running down the cerata — those candle-like projections along the animal’s back, used for respiration.

The northern opalescent nudibranch, or Hermissenda crassicornis, was once thought to occur all over the west coast. But in 2016, genetic analyses revealed that there were actually two west coast species: H. crassicornis, occurring from Alaska to northern California, and H. opalescens, occurring from northern California to Mexico. The southern species appears the same, but it doesn’t have white lines running down the cerata — those candle-like projections along the animal’s back, used for respiration.To avoid confusion, the northern opalescent nudibranch is sometimes referred to as the “thick-horned nudibranch” in the area where the two species overlap. The “horns” are actually a pair of large tentacles, each with a tiny eye at the base. Behind the tentacles are a pair of sensory organs called rhinophores, used to “smell” prey. This species is so good at smelling that it can use the unique chemical signatures of its favorite prey species to pinpoint their locations — a skill known as chemotaxis.

|

|

Photo of Hermissenda crassicornis

by Minette Layne, Seattle, Washington. This file was downloaded from Wikipedia and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. |

Movable feast

|

Dorsal

(top) view of a northern opalescent nudibranch crawling in a glass petri dish.

Photo courtesy of Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu |

At a holiday buffet, this nudibranch would certainly be a member of the Clean Plate Club. In lab tests, it eats pretty much anything offered, including tunicates, worms, crustaceans, small clams, and even dead things. However, its prey items of choice are cnidarians such as hydroids, sea anemones, and sea pens (in Puget Sound, it is a main predator of the orange sea pen, Ptilosarcus gurneyi). These cnidarian prey contain a secret ingredient that is at the top of the nudibranch’s wish list — stinging cells called nematocysts. The nematocysts don’t hurt the sea slug, but pass directly through to its cerata, making it toxic and distasteful to potential predators. For this reason, it doesn’t have camouflage and doesn’t need it…the bright colors warn predators to nibble at their own risk!

|

|

A northern opalescent nudibranch crawls across

an encrusted rocky habitat amongst snails and chitons. Photo by Kirt Onthank, August 2007, wallawalla.edu. |

Naughty or nice?

Beneath the northern opalescent nudibranch’s cheery exterior lies the heart of a true humbug. When one nudibranch touches another of the same species, a fight is imminent, complete with lunging and biting (including biting off chunks of the other’s head — ouch)! In some cases, the winner of the altercation eats the loser.

Despite their violent tendencies, these feisty critters can have a positive impact on human lives by sacrificing their own. They are easily reared in labs and have been used extensively for biomedical and behavioral research, including learning and memory studies and studies on lead toxicity. Maybe every grinch has a softer side after all.

By Dany Burgess, Taxonomist, Environmental Assessment Program

Despite their violent tendencies, these feisty critters can have a positive impact on human lives by sacrificing their own. They are easily reared in labs and have been used extensively for biomedical and behavioral research, including learning and memory studies and studies on lead toxicity. Maybe every grinch has a softer side after all.

By Dany Burgess, Taxonomist, Environmental Assessment Program

Critter of the Month

Dany Burgess is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.

No comments:

Post a Comment